What Is Really Driving Australian House Prices: Population Growth or Capital Gains Tax?

/What Is Really Driving Australian House Prices: Population Growth or Capital Gains Tax?

This question comes up every time house prices rise.

Politicians blame tax settings. Commentators point to capital gains tax discounts and negative gearing. Social media simplifies it further and says “just remove the tax concessions and prices will fall”.

It sounds neat. It is also wrong.

If you strip away the politics and look at how property markets actually move, the answer is much simpler.

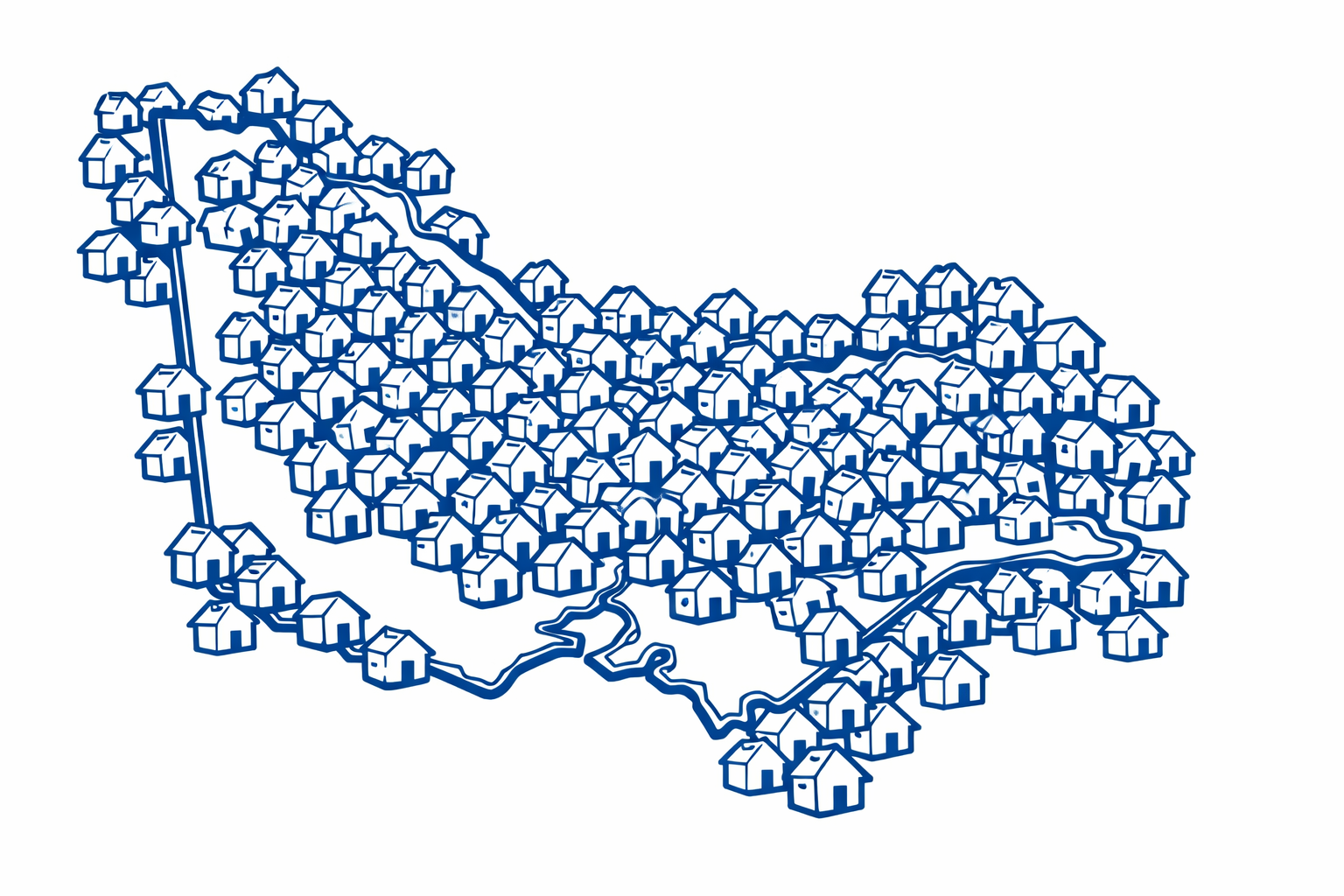

House prices rise when demand consistently exceeds supply. In Australia, the single biggest source of that demand pressure is population growth.

Population growth is the engine, not the side issue

Every additional person needs somewhere to live.

Not every person needs to own a property, but every person needs a roof. That means demand appears first in rentals and then flows through to ownership.

Over the last decade, Australia has added population faster than we have added dwellings, particularly in established capital cities like Melbourne and Sydney. Net overseas migration, combined with longer life expectancy and smaller household sizes, has quietly tightened the market year after year.

This matters more than interest rates, more than lending policy, and far more than tax settings.

When demand keeps arriving and supply cannot keep up, prices rise. It is that simple.

This is also why prices can rise even when borrowing is harder.

Demand does not vanish. It queues.

People share housing longer, stay with family, or rent for longer periods, but they do not disappear from the system. When conditions ease, that demand moves forward again, often pushing prices higher in a short period.

Why capital gains tax gets blamed anyway

Capital gains tax is easy to point at because it feels tangible.

The 50 per cent CGT discount for individuals encourages longer holding periods. That does have an effect. It reduces turnover and means fewer properties come to market at any one time.

But it does not create demand.

CGT does not bring new buyers into the market. It does not create households. It does not increase population. It simply affects when existing owners decide to sell.

At best, CGT is a secondary factor that slightly tightens supply during growth periods.

It is not the reason prices rise across entire cities, including owner occupier suburbs with very low investor participation.

Negative gearing sits in the same category

Negative gearing can increase investor activity at certain points in the cycle, particularly when prices are already rising and rental yields are strong.

But it is not the driver of long term price growth.

If it were, prices would have collapsed during periods when investor lending dropped sharply. That did not happen.

Owner occupiers kept buying. Renters kept competing for housing. Prices stabilised or dipped briefly, then resumed their upward trend as population pressures continued.

What happens when supply actually meets demand

We have seen this before.

In locations where supply genuinely catches up, prices flatten. Rents ease. Competition drops.

This has nothing to do with tax reform. It happens because there are enough dwellings for the number of people who need them.

The problem is that this balance is rare in Australia’s major cities.

Planning delays, infrastructure constraints, construction costs, and political resistance to density all limit how quickly new housing can be delivered where people actually want to live.

The uncomfortable reality policymakers avoid

Australia effectively runs a population policy without a matching housing policy.

Governments are very good at increasing population. They are far less effective at ensuring enough housing is delivered in the right locations, at the right time, and at a price people can afford.

Tax changes are easier to announce than planning reform.

They also make for better headlines.

But adjusting capital gains tax or negative gearing without addressing supply and population settings does not fix the underlying problem. At best, it reshuffles who owns property. At worst, it reduces rental supply and pushes rents higher.

So what is really driving prices up

Population growth is the engine.

Housing supply constraints are the bottleneck.

Tax settings influence behaviour around the edges, but they are not the cause of long term price growth.

Until Australia consistently builds more dwellings than new households are formed, prices will continue to rise over time.

You can change the tax settings. You can change the rhetoric.

But unless supply gets ahead of demand, the direction of travel does not change.

This is not a political opinion. It is a structural one.

And it is the part of the debate most people would rather avoid.